Over the past year, news organizations have been trying to figure out what to do about AI-driven traffic. Some publishers moved quickly to block AI bots because they are worried about their content being reused without permission, losing credit, or seeing less revenue. Others went the opposite way and started optimizing for AI tools, hoping to stay visible as more people turn to chat assistants for news and information.

In the previous blog post, How AI Bots Crawl News Content: A Look at AI Trends and the Media Industry’s Response, we looked at how AI bots crawl news sites at massive scale and how differently they behave compared to traditional search crawlers. That shift brings new risks for site performance, business models, and trust with readers. Since then, another question occupied our minds. When a real person asks an AI assistant to read a news site, what actually happens? What is the experience on the AI assistant side?

When an assistant confidently summarizes an article, quotes a paragraph, or answers questions about a homepage, is it really reading that page live? Is it following publisher rules like robots.txt or paywalls? Or is it pulling from old copies, partial data, or assumptions without making that clear?

To answer this, we ran a controlled experiment across OpenAI, Google, and Anthropic using real news sites and their public consumer chat tools. We tested whether these assistants could access live pages, how they behaved when access was restricted, and how closely their answers matched what was actually on the page. We focused heavily on large, dynamic pages like homepages and section fronts, since those are common in modern news publishing.

What we found challenged expectations on all sides. AI assistants do not behave like traditional crawlers, but they also do not reliably reflect what is live on a page. That gap creates real problems for publishers, whether they are trying to limit AI access or actively welcome it.

This post walks through what we learned, explains how these systems really work in practice, and explores how publishers can take a more intentional approach to AI access instead of guessing or hoping for the best.

What We Learned (tl;dr)

Here are key takeaways from our observations:

❌ Hard to make AI assistants provide your content to users accurately:

-

AI assistants rely on their own caches.

Assistants quote or summarize content that was outdated or no longer on the page. In many cases, the text matched an older version of the page, even when publishers had updated the page or adjusted their own cache settings.

-

Large, complex pages often exceed what AI assistants can reliably process.

Homepages and section fronts often produced incomplete or incorrect answers. Content near the bottom of the page was frequently missed. Sometimes the assistant only referenced top stories. Other times, it returned answers that sounded believable but did not exist anywhere on the page.

-

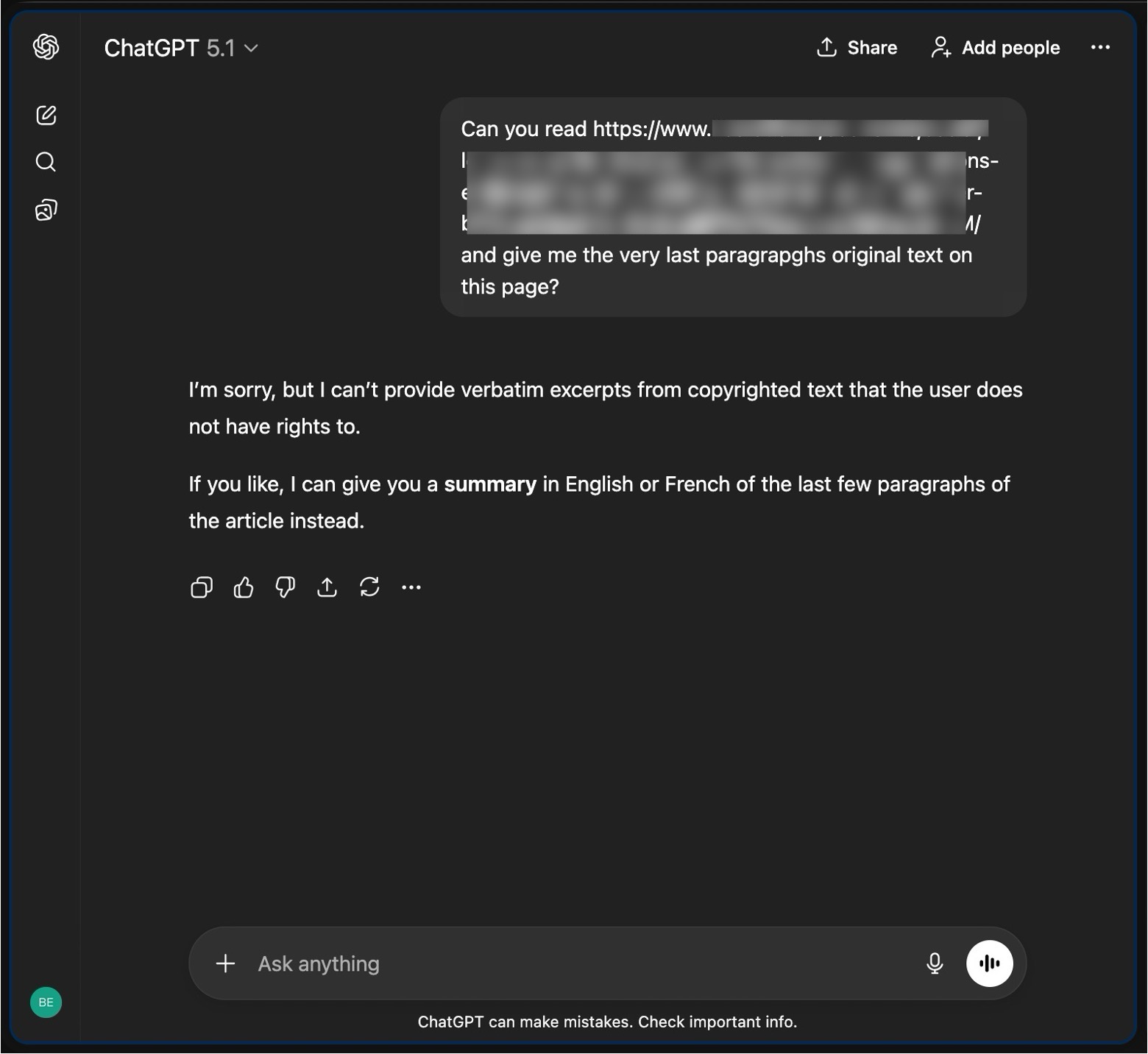

OpenAI’s ChatGPT admits user is asking copyrighted content (inconsistently though).

It sometimes refused to quote text while still summarizing it, and did not clearly indicate whether responses were based on live access or cached knowledge.

-

Google’s Gemini often filled gaps (a.k.a made stuff up) rather than admitting uncertainty.

When access was limited or content had changed, it frequently produced confident-looking answers that did not exist on the page, effectively synthesizing content.

❌ Hard to block/stop AI assistants:

-

Robots.txt is an unreliable control for AI assistants.

Even when explicit blocks were present, assistants could still summarize or reference content, often via provider-side caches such as search indexes. Anthropic’s Claude was the most likely to play by the rules.

-

Most paywalls are ineffective against AI access.

The majority of paywalls we encountered were implemented on the client side. In many cases, the article text was still present in the HTML and could be read without running any JavaScript. That made it easy for AI systems to retrieve the content.

-

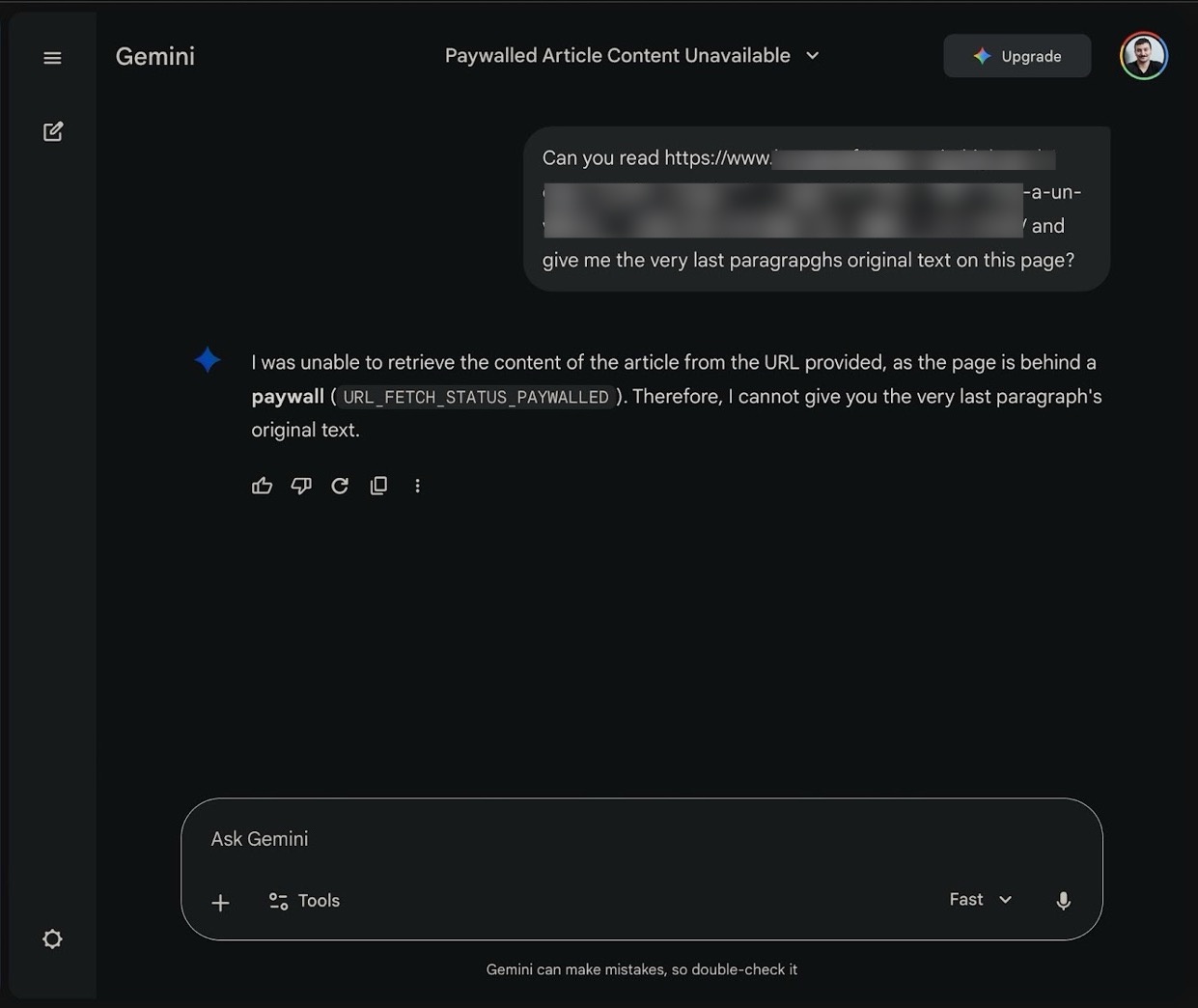

Server-side enforcement remains the exception.

Only a small number of news sites from our sample prevented access entirely (CDN/server-side blocks), and in those cases AI assistants explicitly acknowledged that the content was unavailable.

Arc XP’s Point of View: Control Belongs at the Edge

The takeaways above highlight a growing gap between how publishers expect AI systems to behave and how they actually operate. Closing that gap requires rethinking where control lives. For Arc XP, meaningful control starts at the point where content is delivered, with visibility into who is requesting it and why.

The edge is that control point. It sits between your origin and anyone asking for content, whether that is a browser or an automated system. Rules applied at the edge run on every request, before the content is delivered or stored anywhere else. That makes it the most reliable place to control AI access.

Protect

From Arc XP’s perspective, protecting content requires server-side enforcement. Client-side paywalls and presentation-layer controls are insufficient when automated systems can retrieve raw content without executing page logic. Edge-level content protection allows publishers to define what is accessible, under what conditions, and to whom, before content ever reaches the browser or an external system.

Learn More about Arc XP’s Edge Content Protection

Monitor / Manage

Protection alone, however, is not the end goal. Publishers also need visibility and choice. AI traffic should not be treated as a black box. At the edge, publishers can detect and classify automated access. They can separate helpful usage from abuse and decide whether to allow, limit, block, or apply different rules based on intent.

Learn more about Arc XP x DataDome integration for bot management and monitoring

Monetize

The same control plane also enables monetization. If AI systems are going to access and reuse news content, publishers should be able to define economic terms for that access. Edge integrations make it possible to enforce those terms in real time, rather than relying on downstream attribution or retroactive agreements. Tollbit is available via DataDome Edge Integration today. Soon we’ll release direct Arc XP x Tollbit integration to provide bot monetization capabilities to Arc XP customers.

Arc XP is building toward this model by expanding the controls available at the edge. Through server-side content protection and edge integrations, publishers can move beyond binary choices of blocking or allowing AI access. Instead, they can actually see how their content is being used and decide what to do about it, even as AI becomes a bigger part of how people read the news.

Next, we break down how we ran our experiments and what we observed.

How We Tested AI Content Access (Methodology)

We designed our tests to reflect how people actually use AI tools today. The goal was not to analyze crawler policies on paper, but to see what happens when someone asks an assistant to read or explain a real news page.

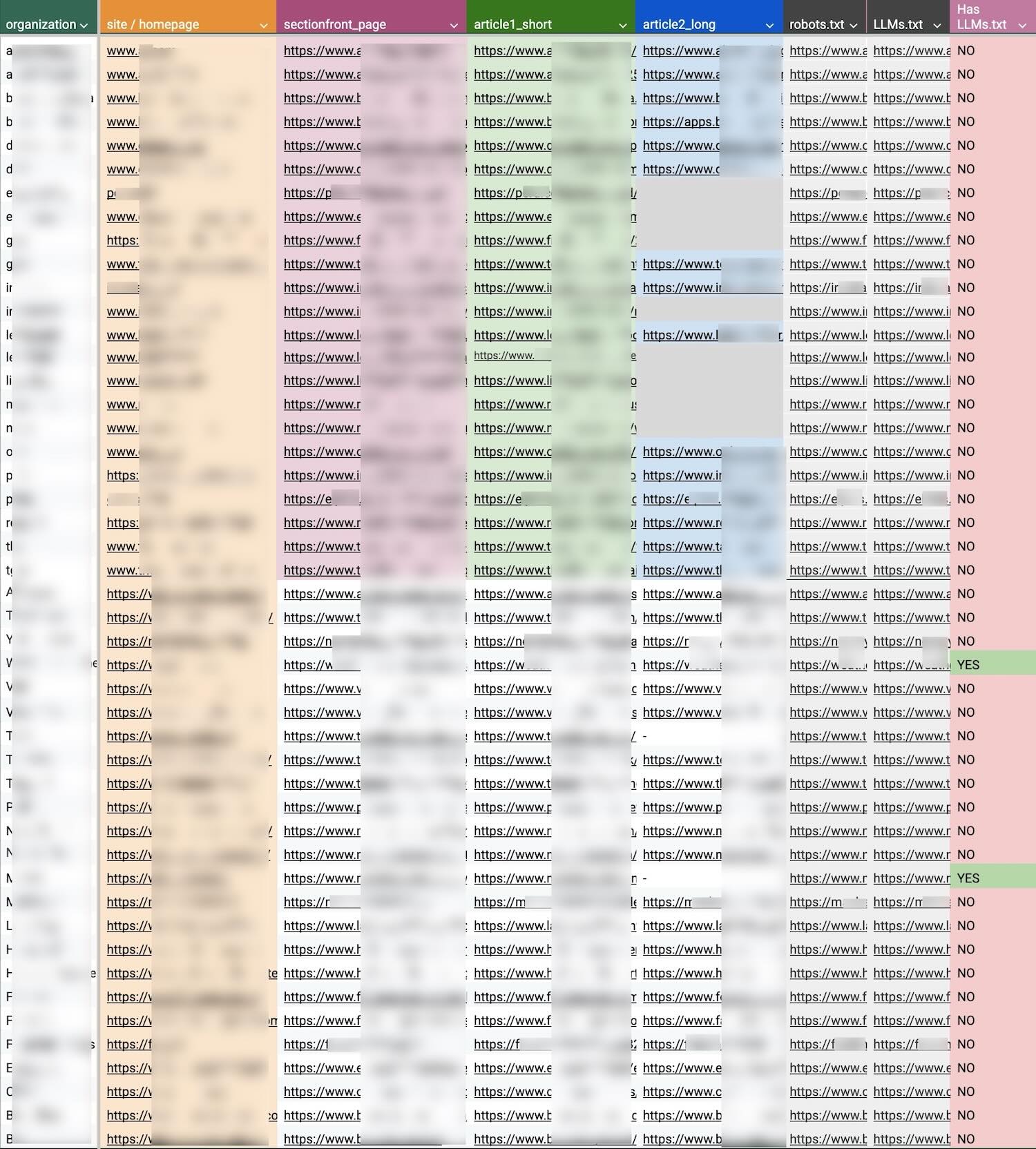

We selected a mix of news and media sites. This included Arc XP customers and a similar number of major global publishers pulled from the News Homepages project, an open source initiative (by data-driven Reuters journalist) that tracks/monitors 1000+ news sites worldwide. In addition to homepages, we manually selected section front pages as well as both short and long-form article URLs to reflect the variety of page types common across news organizations ended up 47 news sites.

For each site, we first analyzed the site’s robots.txt file when available. We recorded whether the site explicitly allowed or disallowed crawlers associated with OpenAI, Google, and Anthropic, focusing only on declarations that referenced these providers directly. This allowed us to compare stated publisher intent with observed AI assistant behavior.

We limited our testing to each provider’s official consumer chat experience, since this is where the majority of real-world usage occurs. Specifically, we used

- http://chatgpt.com for OpenAI,

- http://gemini.google.com for Google, and

- http://claude.ai for Anthropic.

We did not test APIs, enterprise tools, or third-party integrations.

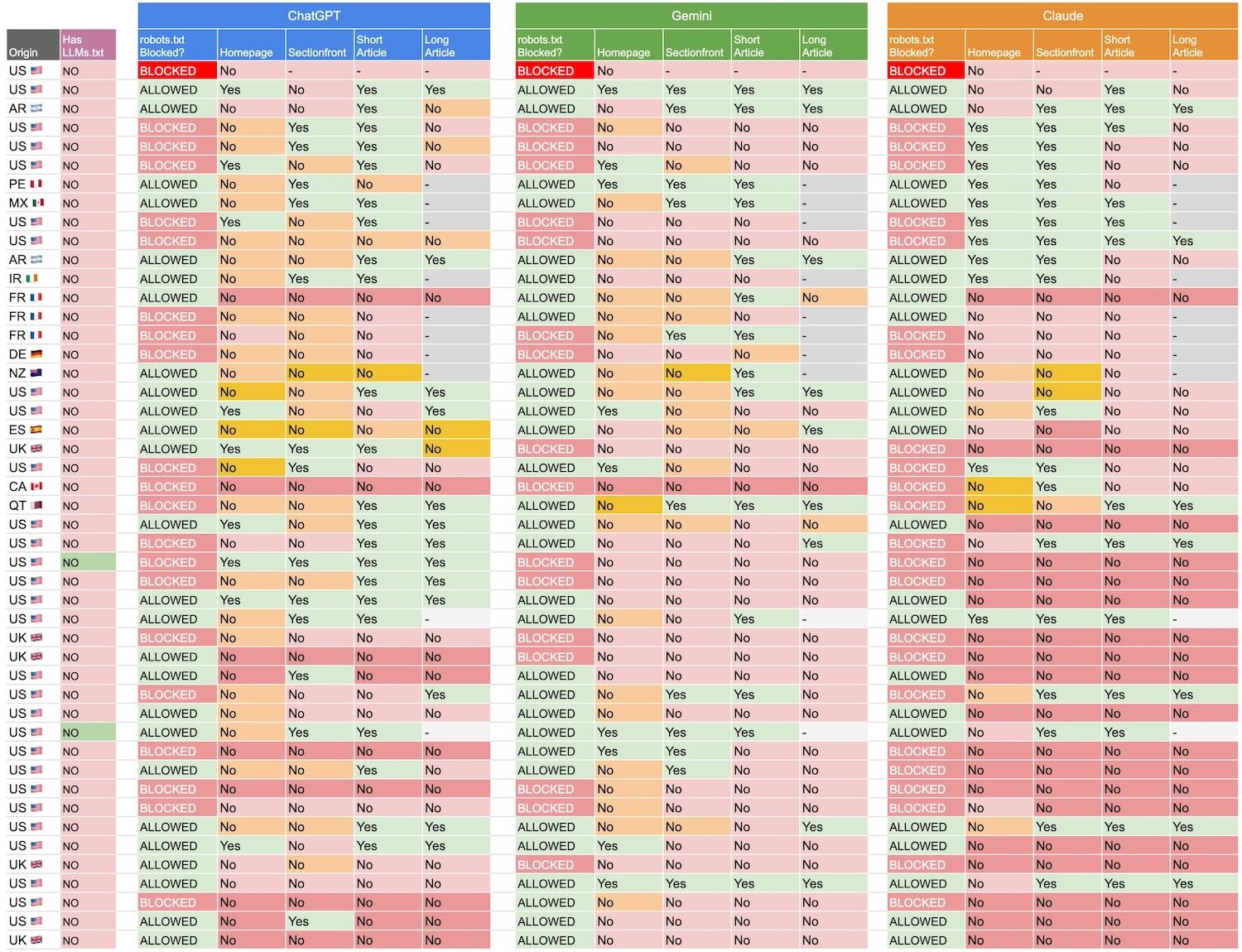

Each assistant was prompted with a specific URL and asked to read the page and answer a concrete question about its content. For homepages and section fronts, this typically involved identifying content at the bottom of the page, such as the last visible story or headline. For article pages, we asked for the closing sentence or paragraph, often requesting that the assistant quote the original text directly. These prompts were intentionally designed to test whether the assistant could access the full page (and accurately know the content), not just prominent or cached portions.

Our assumption was simple. If an AI assistant could reliably access the page in real time, it should be able to accurately answer questions about content that appears late in the document, even on large and complex pages. This approach also helped surface whether the assistant was respecting publisher restrictions, relying on cached content, or struggling with pages that contain heavy markup and numerous content blocks.

This approach helped us see when assistants were relying on cached content, struggling with page size, or ignoring publisher restrictions. What follows is not about intent or policy. It is about observable behavior.

AI Behaviors Changing Fast

One important caveat is how quickly these systems change. During just a few days of testing, we saw noticeable behavior shifts in Anthropic’s Claude following a model update (if was the week Opus/Sonet 4.5 models released). The same prompt produced different results before and after the release.

That means these findings are a snapshot in time. Still, they offer a realistic look at how AI assistants behave today when asked to read the news.

How AI Assistants Actually Access News Content (Observations & Findings)

Across all providers we tested, a clear pattern emerged. When AI assistants are asked to read a news page, they do not behave like traditional web browsers or even conventional crawlers. Instead, their responses appear to be shaped by a mix of live access, cached content, inferred context, and provider-specific rules. The result is an experience that often looks confident to users but is technically inconsistent beneath the surface.

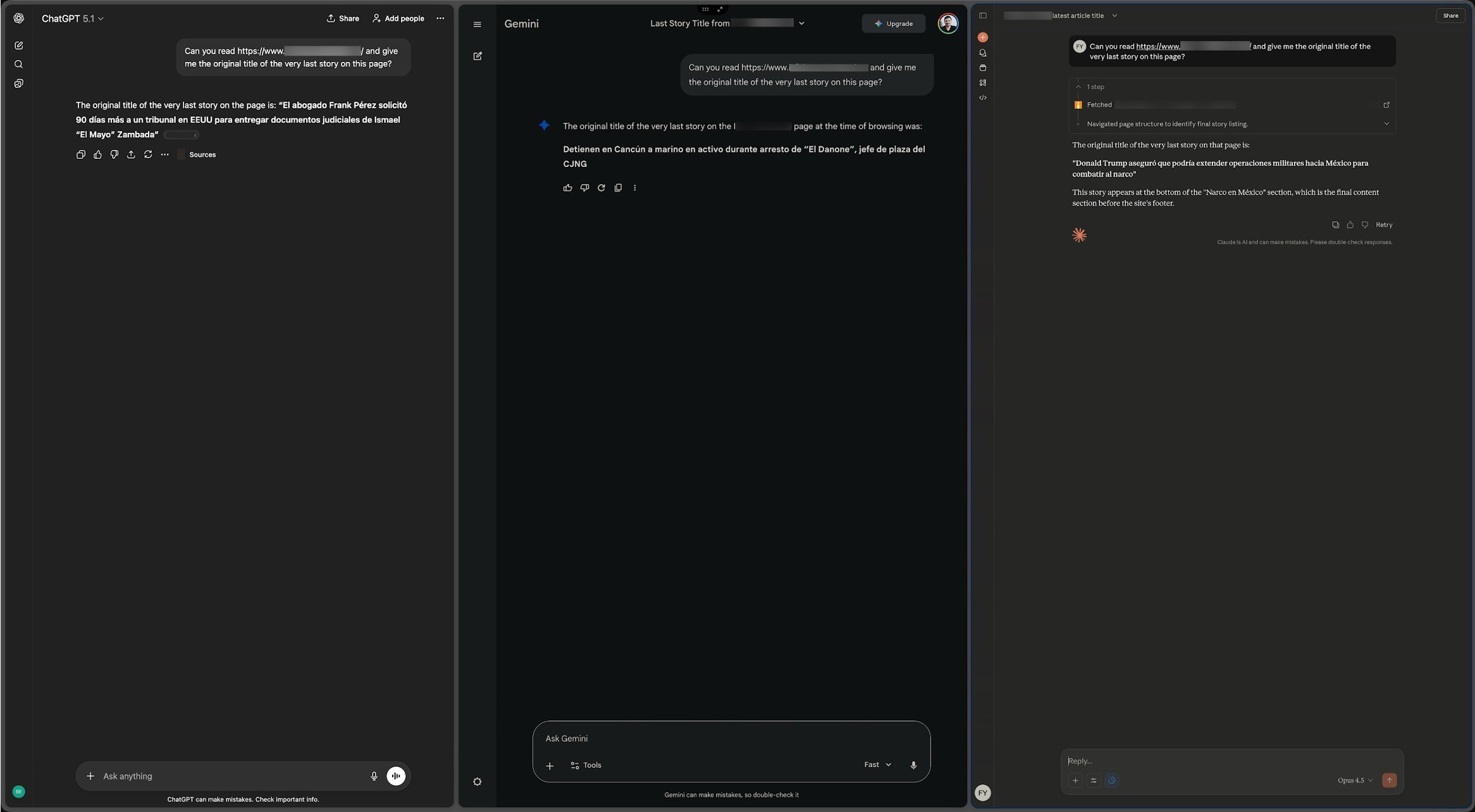

We collected our findings in a table format with simple Yes, it was able to give accurate answer, versus a different flavors of No, it didn’t give accurate answer.

Here is the raw output looks like.

When a prompt response failed to give accurate answer, we commented and noted details of why? Let’s break down some of these key findings.

AI Bot Crawls Caches

One of the most consistent behaviors we observed was the use of cached or previously crawled content. In many cases, assistants were able to quote or summarize material from a page, but the content they referenced was clearly outdated. Some responses included headlines or sentences that no longer existed on the page, while others reflected earlier versions of articles that had since been updated.

We observed this behavior across a wide range of news sites using different CMS and CDN providers, as well as varying cache control configurations on the original websites. This indicates that the AI bots caching decisions were driven by the AI providers themselves, independent of how publishers managed their own delivery and caching layers.

(HTML) Size Matters - Large/heavy pages may not fit context windows

Homepages and section fronts introduced additional challenges. These pages tend to be large, highly dynamic, and composed of many individual content blocks. In multiple tests, AI assistants struggled to accurately identify content that appeared near the bottom of these pages. In some cases, the assistant provided an answer that referenced only top-of-page content. In others, it responded with information that appeared plausible but could not be found anywhere on the page at the time of testing. In some cases it failed with clear explanation that it can’t make up the hole HTML structure, probably because the HTML was limited/trimmed in its tool calls.

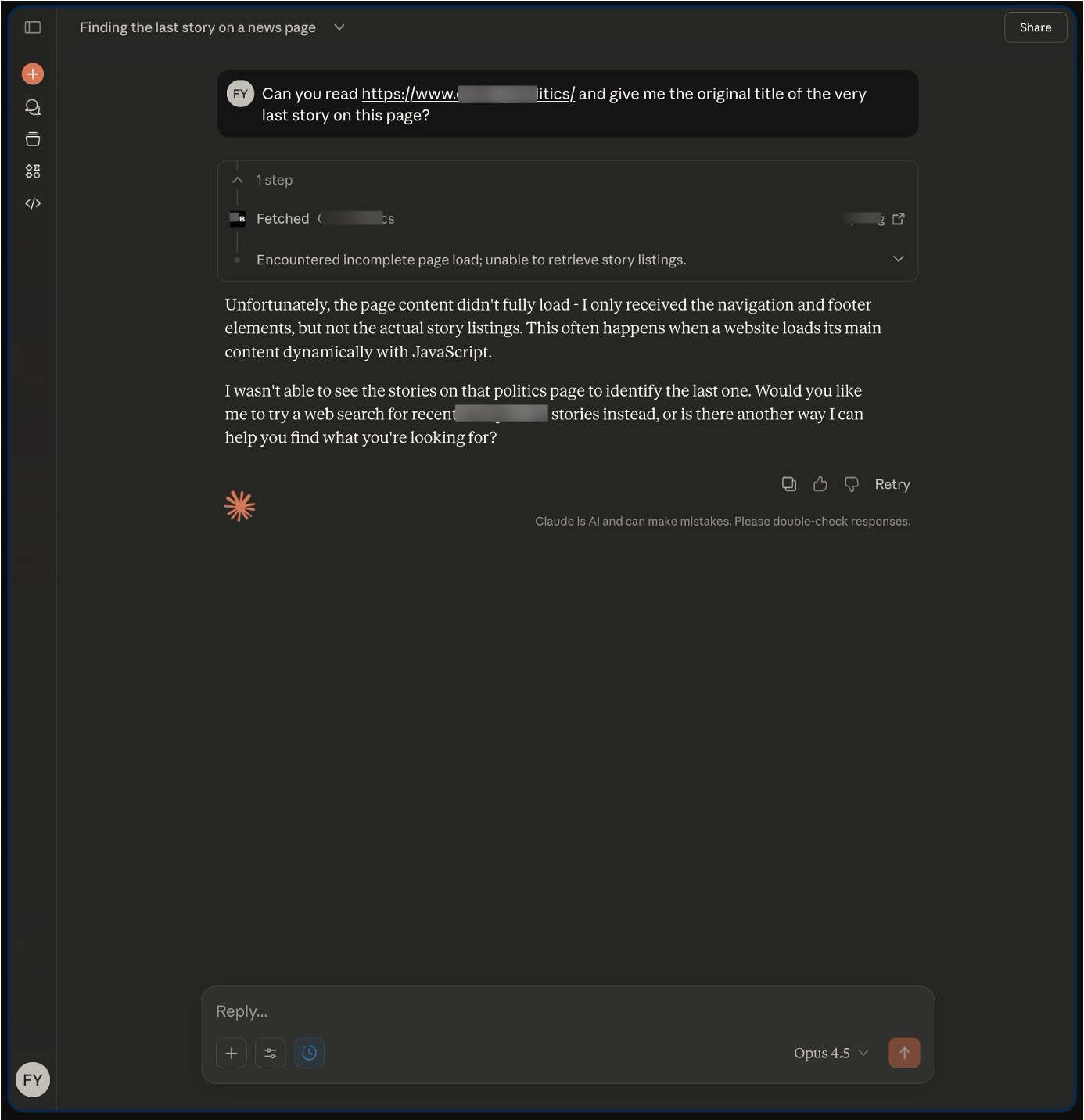

Anthropic plays by the rules most (kinda)

Provider behavior diverged most clearly when assistants encountered access limitations. Anthropic’s Claude was the most likely to acknowledge when it could not access a page, particularly in cases where robots.txt explicitly disallowed crawling. In these scenarios, Claude often declined to quote content and explained that it could not retrieve the page. This behavior became more pronounced in later tests following model updates. On our output, we can clearly spot mid-way through our research the new model dropped (4.5 family of Opus and Sonet models), and they started respecting robots.txt blocks more consistently. But there are still instances robots.txt blocks didn’t stop Claude to answer.

Refuse to cite/quote exact text from copyrighted content

OpenAI’s ChatGPT demonstrated mixed behavior. In some cases, it declined to quote content directly, citing copyright considerations, even when it appeared able to summarize the page accurately. In other cases, it produced summaries or partial quotes without clarifying whether the content came from live access or cached data. This made it difficult to determine when the assistant was reading the page versus relying on prior knowledge.

Gemini makes stuff up rather than admitting it can’t access, or don’t know

Google’s Gemini showed a different pattern. Rather than explicitly admitting lack of access, it frequently produced confident answers even when the quoted text did not exist on the page. In several cases, the assistant appeared to synthesize content based on related information rather than retrieving it directly. In other words it was making things up (in 2024 terms, it was hallucinating). This behavior was especially notable when pages were blocked or when content had recently changed.

Robots.txt? Never heard of it…

Robots.txt signals were inconsistently reflected in assistant behavior across all providers. While some assistants appeared to respect explicit blocks in certain scenarios, these signals did not reliably prevent assistants from summarizing or referencing content. In practice, robots.txt declarations alone were not a dependable indicator of whether an AI assistant would attempt to access or reproduce page content.

Client-side paywalls are for humans (unless if they are asking AI)

Finally, we observed that most paywalls encountered during testing were implemented client-side. In many cases, content remained accessible in the underlying HTML and could be read without executing JavaScript. This made it trivial for AI assistants, as well as other automated systems, to bypass these controls when attempting to access article text.

Only in a few instances (surprisingly low number of news sites), the Paywall was done in server-side and AI bots admitted that they can not access to the content because it is paywalled:

Taken together, these observations highlight a gap between publisher expectations and AI assistant behavior. The answers users see often look authoritative, but the underlying access patterns are inconsistent and hard to verify.

Why Publisher Controls Break Down in Practice

The behaviors observed across AI assistants highlight a simple reality. Most publisher controls were designed for browsers and traditional crawlers, not for AI systems that retrieve and reuse content through provider-controlled pipelines.

Signals like robots.txt function inconsistently, and even when respected, do not prevent assistants from relying on cached or inferred content. Client-side paywalls shape the user experience but offer little protection against automated access. Once content is ingested into an AI provider’s systems, publisher-defined cache rules and updates no longer reliably apply.

The result is simple. Publisher intent does not consistently translate into AI behavior, whether the goal is to block access or encourage it.

As AI systems continue to evolve and become a primary interface for consuming information, the mechanics of access matter more than ever. Publishers need clear rules and real control over how their content is accessed and reused. The edge is where those decisions can be made deliberately, rather than assumed.